The crisis in Portugal’s biggest bank, Caixa Geral de Depósitos, and how it explains the crisis the country itself has faced in last few years.

The small, remote town of Almeida doesn’t make the news very often. Closer to Spain than to Portugal’s capital city of Lisbon, Almeida lives with all the benefits and evils of the relative isolation that every hinterland town in Portugal either enjoys or must endure. But on April 12, a protest against the upcoming closing of the local branch of Portugal’s State-owned bank, Caixa Geral de Depósitos – usually known as CGD or simply Caixa – caught the media’s attention. CGD was undergoing a restructuring process, that in the coming years will encompass a capital injection of more than €5 billion (2,7 of them directly by the State, a €1 billion perpetual debt bond sale, and €960 million in “Contingent Convertibles”, bonds convertible into equity once a specified event – the “trigger” – occurs, basically amounting to a debt cancelation by the State), a staff reduction plan and the closing of a number of branches throughout the country. Almeida was about to lose its own, and the town’s population wasn’t happy.

If the protesters’ aim was to convince Caixa to reverse course – and it obviously was – they fell short. Fourteen days later, on the eve of the scheduled closing date, about fifty people – including the Deputy Mayor – entered and refused to leave the branch’s premises until the decision to close it was overturned. Outside, just beside the small, welcoming park where people spend most of their afternoons hiding from the sun, complaining about their health and sharing gossipy details about the neighbors everyone knows, a few more voiced their support. They were mostly elderly, poor people in old, worn-out clothes, some holding canes and one wearing a suit and hat like no one of any other age would. Spotting the crew of one the TV networks, an elderly lady, probably in her 60’s, approached the reporter, and announced: “this will go all the way. The municipal government is committed, the population is committed, this will go all the way”. “If we have to”, she continued, “we’ll go to Lisbon”. “We will go wherever we have to”, the lady said. The only place they didn’t want to have to go to was the nearest remaining Caixa branch, in the neighbouring town of Vilar Formoso. Many of people interviewed by every TV network gave the reason why: Almeida is an aging town, and people don’t want to have to go all the way there to take care of their affairs. Some of them don’t have cars, public transportation is lacking, and having to do regular visits to Vilar Formoso to collect their pensions, check their balance or just to find an excuse to exchange a few words with the familiar lady who works in the bank is not something that is particularly appealing to them.

“We’re being indiscriminated”, one of the protesters said, not realizing that was the wrong word. Another, a woman it her seventies, said the whole thing was all “an inconvenience”. A gentleman said people “felt deceived”. Another explained that the older people in town want help to cash and deposit money, and they don’t trust outsiders to do it. Hours later, as the protest came to an end when Caixa scheduled a meeting for May 2 to discuss the matter, everyone chanted a luta continua! – “the fight won’t stop”.

***

Two months earlier, after being nominated as CGD’s President, Paulo Macedo, a former Health Minister for the 2011-2015 center-right coalition government of PSD and CDS chosen by the current center-left government of the Socialist Party to lead the State-owned bank through its restructuring process, said that the latter “is a great opportunity” that was “being given to us all” to “be a part” of the “institution’s relaunch”, but that it was “also a great responsibility”, as “the country is undertaking a significant investment in Caixa, in a time of scarcer resources, and it will justly demand that the former should be well applied”. His goal, he said, is to make CGD a “solid, profitable and confidence-generating” bank, “which is why”, Macedo warned, “it is time to execute, act, work and for us to focus all our energy in the recapitalization and restructuring of our institution, but also in improving our services to our clients and in creating value, allowing us to face the future with optimism and confidence”.

“If we fail”, he added, “we will hardly be given another similar chance”.

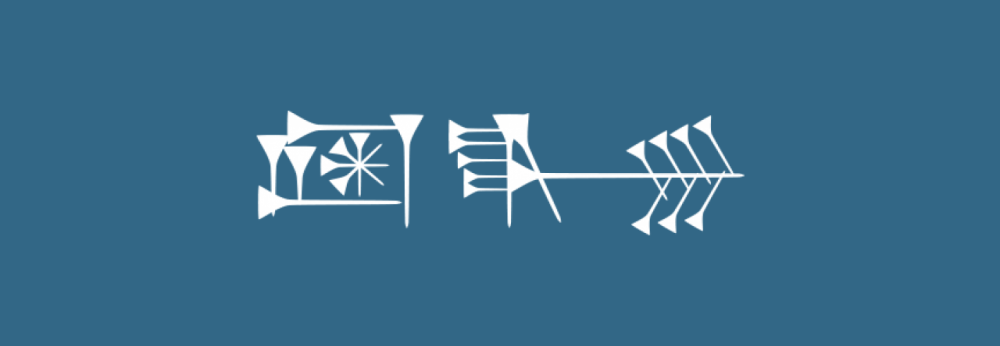

When it was created in 1876 by the government of the day, Caixa was devised – as usual in Portugal, by translating into Portuguese a French model, the Caisse Générale des Dépôts et Consignations – as an instrument to respond to the banking crisis the country had faced and that had put the fulfillment of the State’s financing needs in jeopardy, using private citizens’ savings and the obligatory deposits, whether in cash or sovereign debts bonds, that the State charged people (court bails, taxes), to be applied “in a productive way” – that is, by feeding the budget and the chronically hungry State coffers.

In 1892, however, another bankruptcy hit the country – and CGD – like a meteor. In the previous decades, an emigration wave to Brazil and the money those migrants sent back home gave Portugal some credit in the London and Paris stock markets, which allowed the government to sell debt bonds and get the money for its economic policies of infrastructure spending (and buying off internal political clienteles). But when a republican revolution sent Brazil into turmoil, and the “Brazilians’” money stopped crossing the Atlantic, that credit disappeared. Caixa tried to fulfill at least some of the country’s budgetary needs, without being in a healthy situation itself. Its profits collapsed, but the bank itself didn’t. Once the bankruptcy was behind Portugal’s back – it took a few decades – CGD seemed to come of age – so to speak – escaping with varying degrees of difficulty the turmoil of the seemingly never-ending national political and economic tribulations, and became Portugal’s largest financial institution.

Once António Oliveira Salazar and his dictatorship took over the country, and his scrupulous, frugal budgetary policy jumped away from the pages of the obscure papers he wrote as a reclusive but politically ambitious Professor of the University of Coimbra into governmental acts, Caixa’s usefulness to the holders of political power did not cease to exist, but it did change: it was now meant to loan – to private investors and the State – its money, in order to achieve what Salazar called the country’s “financial regeneration” and its “agricultural, industrial and social transformation” – in other words, to “stimulate” the economy and intervene in the market to manipulate production levels and prices in such a way that would favor the humors and interests of the government and its preferred clienteles. Forty years later, when Salazar became incapacitated and had to – finally, most must have thought and said to those they were confident would not rat them out to the secret police – give up his power and be replaced by his former-protégé-turned-political-rival Marcello Caetano, CGD (by now already labelled a empresa pública, the bureaucratic, legal term for a “State-owned company”) still played this role, and would keep it as the new President of the Council of Ministers engaged in his “modernization” policy.

After the April 25th 1974 coup that overthrew the dictatorship, the revolutionary ecstasy Portugal succumbed to for the ensuing year and a half was not – despite the many efforts of the groups who lead it – enough to make the country go from the hands of a dictatorship to those of another, but it was still able to do some damage. The government, temporarily controlled – or at the very least very heavily influenced – by the Communist Party, nationalized banks, insurance companies and increased salaries for government employees (in 1978, already with the first democratically elected government in office, the price the country had to pay for the adventure was an International Monetary Fund bailout). Caixa kept its role as an instrument of political power in the manipulation of the economy as a whole, for instance in promoting and facilitating access to credit for buying a house. In 1992, CGD became a stock corporation, but the State remained its sole stockholder. One would think such a legal statute would give the bank a larger autonomy from political power (that was, in fact, the stated purpose of categorizing it as such). But that was far from being true. During the cheap, easy credit boom of the 1990’s and early 2000’s, Caixa was a prime agent in the creation of an excessive debt in Portugal, both in the private and State sectors. In loaning money – as other banks did – to people for buying houses in a country where, to make matters worse, the renting market was far from effective, Caixa – and the financial and political systems as a whole – practically forced them to contract a huge debt burden that might have seemed bearable while interest rates were low and the economy thrived, but would become much less so in the years to come, as would the debt incurred by private companies who saw in the booming construction business an opportunity to get rich, and the huge amount of debt government after government kept getting into to finance multiple infrastructure “projects” that were deemed and sold to the public as “strategic” for the country’s “modernization” and economic development.

In 2008, it would all come crashing down.

***

The financial and political systems’ infatuation with the housing market was not confined to Portugal. In America, banks and politicians alike engaged in or encouraged what would become known as “subprime” loans – credit given out by the banks to clients who ended up being unable to afford to pay back the loans they were receiving. When many of those borrowers did indeed default on their mortgages, house prices fell as quickly as they had been inflated by the subprime bubble, causing huge losses for the banks that had bet heavily in that market. To make matters worse, many of those loans were “bundled” in so-called “mortgage-backed securities” with “prime”, safer, loans, thus diluting their risk. And because each of those securities were then “bundled” with other securities and then sold to increasingly far-off investors, the more unaware they became of the underlying risk of those products as the further they were in the selling-and-buying chain. The result was that investors in Iceland, Ireland, Greece or Germany – just to stick to the Michael Lewis-reported ones – were, probably without even noticing, financing loans to borrowers in Detroit or somewhere in Tennessee that wouldn’t be repaid. Instead of decreasing the chances of losing the money they were lending to “subprime” borrowers, the “securitization” of those loans by American banks ended up exposing the entire world economy to the risk – and the costs – of that imprudent credit.

By all accounts, Portuguese banks were not among the most affected by that exposure. But slowly, the “subprime” crisis turned into a sovereign debt bonds crisis: as banks needed to be bailed out and the economy stalled, governments all over Europe increased their spending levels, for which they had to borrow more money, in some cases to such a degree that the market’s confidence in those countries’ ability to service their debt reached historic lows, causing the interest rates on their debt bonds to take the exact opposite course, and those countries to no longer being able to finance themselves without a bailout by the IMF.

Portugal was one of those countries. In 2011, the “troika” of the IMF, the European Union and the European Central Bank came to the rescue with a €78 billion bail-out package with €12 billion for the banks to use to recapitalize themselves. They badly needed them. Not only they were the largest funders of the debt splurge the government of the day, led by then-Prime Minister José Sócrates of the Socialist Party, currently under investigation for corruption, tax fraud and money laundering, but the “austerity” prescribed by the “troika” and applied by the PSD/CDS coalition once an election threw Sócrates out of power also meant that there was no government –i.e., taxpayers’ – money for the “public-private-partnerships” in infrastructure Portuguese banks had become accustomed to invest in at almost no risk to themselves, as well as other shady deals. To further complicate things, Portuguese banks were themselves heavily indebted, both to each other and abroad, and so they to felt the noose tightening around their necks.

Only one bank declined the opportunity to use the “troika” billions to replenish their coffers: Banco Espírito Santo, commonly referred to as BES. The choice, as it would later become clear, was not motivated by an enviable healthy condition of the bank or the financial group it was a part of, but to a need to keep its books as far away from the inquisitive eyes and minds of the “troika” officials, as they would reveal – as they later did anyway – the many unlawful schemes BES was involved in. The oldest and largest economic group in Portugal, Espírito Santo’s assets were among nationalized businesses during the revolutionary period. In the 1990’s, as governments began to privatize all the companies that had been nationalized, the “Portuguese political and economic elites”, the economic historian Luciano Amaral explains in his book about the group, “wanted to rebuild national economic groups as a way to compensate them for what had happened”, and proceeded to “reconstitute” them under “monopolist or at best oligopolistic conditions”, designed to make them successful at the expense of anything else, under the belief that the Portuguese economy required successful Portuguese-owned big economic groups. When BES was privatized, Amaral writes, “the number of banks in the market had become practically half of those that existed in 1975”, and “that numbered kept going down until 2000, thanks to a concentration orchestrated between the State and the financial groups”. Not only, he concludes, “was the privatization carried out within a more concentrated market” than the one it existed at the time of the nationalization, it also “did not prevent the continuation of such a concentration nor did it introduce competition factors”. And the same happened in other sectors were the group had important concerns, like telecommunications, oil or electricity. All of them “saw rising profits thanks to a shrinkage of competition” in their respective markets.

When the economy collapsed, so did BES: governments had less money to spend, which also meant less contracts to be handed to BES-owned companies or BES-financed projects; loans that had been granted in the previous, leaner years were now on the verge of default, and, as Amaral writes in his book, the family had, in order to keep the group in its hands, “often used unorthodox management and financing methods” – “unorthodox” here being an euphemism for “fraudulent” (the head of the group, Ricardo Salgado, is now under investigation by the Portuguese judicial system for alleged criminal practices with BES). By the summer of 2014, BES couldn’t keep its troubles at bay any longer, and everything was over: the group was broken up, and BES gave way to Novo Banco – the “New Bank” – which theoretically kept its predecessors “good assets” while the “toxic” ones were thrown into a “bad bank” designed to bury them.

Among the exposed to those “toxic” assets was Caixa. In the summer of 2014, the Lisbon daily Público reported that CGD had €300 million stuck on several companies of the Espírito Santo Group. Almost a year later, it was revealed that in fact Caixa was owed €410 million by those companies. That – together with the fact that the European Union had changed its rules for state bailouts of financial institutions, reducing the likelihood of such operations taking place, thus threatening the future prospects of banks under duress – surely contributed to Fitch – the rating agency – downgrading CGD’s bonds to a “BB-” investment grade just a few days later.

The bad news for Caixa seemed to pile up: in 2013, before the changes to those European rules, it had been granted a substantial – €1.650 billion – loan by the State; in July of 2015, then Prime-Minister Pedro Passos Coelho complained that while other banks – BPI and BCP – had already started to pay their own loans back, CGD wasn’t yet “able to obtain results that would allow it to pay a fraction” of the amount it had borrowed. “I’m worried”, Coelho said, and he was right to be.

By November 2015, Caixa did report a €3,4 million profit in the year’s first nine months. But that figure amounted to a 93% fall from the profits it had earned in the same period of the previous year, and it had only been achieved by selling much of its stake in insurance companies Fidelidade, Cares and Multicare, a source of revenue the bank obviously would not be able to resort to in the future. Once the year was over and the books were properly looked over, it turned out that CGD finished 2015 with a €171 million loss. In the following three months, it would report a €74 million loss, despite a 5,5% cut in operational cuts and a 4,7% cut in personnel costs.

Caixa was suddenly faced with acute and urgent capital needs. It needed not only to begin to repay the loan it had took from the State, but also to comply with the new ECB capital requirements. But by June 2016, the news coming out was that CGD ran the risk of reporting more than €2 billion in non-performing loans to groups like Espírito Santo and Lena (both involved in the investigation concerning Sócrates). “If it was a private company”, Amaral wrote in his Correio da Manhã column, Caixa would have filed for bankruptcy long ago”.

Rumors that the bank would have to fire people and close branches began to circulate. The Prime Minister – no longer Passos Coelho but the current leader of the Socialist government, António Costa – felt the need to publicly state that any recapitalization would be done exclusively with public money. “We’re going to keep Caixa 100% public, 100% state-owned, and 100% financed with the necessary capital to fulfill its mission”, Costa guaranteed. A week later, someone leaked the information that the amount the government “might” have to spend to do what Costa promised would be €5 billion, to “enlarge the financial pillow” to accommodate the impact of non-performing loans. The Treasury State Secretary, Ricardo Mourinho Félix – José Mourinho’s cousin, believe it or not – reassured the unions that although 2500 workers would cease to work for Caixa, none would be fired, but would simply come from the pool of people that would retire anyway or of people that would be eligible for an early-retirement package, but the unions didn’t trust him. To them, it was all a ploy to “erase Caixa’s credibility” so that private banks could “grab” CGD’s share of the market.

Meanwhile, the ECB was far from confident in Caixa’s restructuring plan, finding the €5 billion figure excessive and unaccounted for. In August, the need for that amount of money became clearer, as the bank reported a €205 million loss and a 28,3% increase in non-performing credit exposures. Two weeks later, the plan was approved by the European Commission. Just a few days later, news surfaced that CGD had failed the ECB’s stress tests, as these shown the bank would need €2 billion euros of additional capital to survive the direst scenario anticipated in those tests.

To make matters worse, another crisis hit Caixa. In March 2016, António Domingues of Caixa’s competitor BPI accepted an offer to become CGD’s new president. He did, however, require that he and his team would be exempted from the salary restrictions applied to public administration workers and from the need to disclose their personal financial information to the Constitutional Court. The government accepted those terms, even though – many would and did argue – the law would not allow those terms to be abided for. Once they became public, the government could not contain the controversy and the public outcry against the privilege Domingues and his team had been afforded with. Immediately, Costa tried to backtrack, claiming the government had not acquiesced to Domingues’s request. After months of pressure and turmoil, Domingues got fed up with it all, resigning from his position, clearing the way for Macedo. In the meantime, CGD’s restructuring plan was still waiting to be put in place. By the end of the year, and with Macedo already on board, Caixa would report a €2,7 billion loss.

Last March, CGD managed to sell the perpetual debts bonds the restructuring plan depend on, but only at a 10,75% interest rate. Costa welcomed the outcome, stating the operation had been a “success, first because of its originality, and secondly because it had a demand four times larger than the existing offer”. What the Prime-Minister declined to mention, however, was that it meant that Caixa would have to pay almost €100 million in interest a year, when the profits projected by Macedo and its team for the future are still nothing but wishful thinking. Between January and March, for instance, CGD lost another €39 million, as two different rating agencies – Moody’s and DBRS – advised against investing in the bank.

Macedo was not discouraged, or at least he did not show himself to be in public. On April 12, as the residents of Almeida took to the streets for the first time to protest against the announced closing of Caixa’s local branch, Macedo was speaking before the Portuguese Parliament in Lisbon. “The plan provides an answer to the big issues” concerning the bank, he said: “more solidity, more efficiency, more operational focus”. A state-owned bank, Macedo said, “doesn’t mean it has to lose money”.

Up until now, it still is.

***

Even without going further back in History – to the times before the 19th century, back to when the wearers of the Crown held the Kingdom as private property they could dispose of as they wished and use to favor whoever they thought they should – ever since 1851, after the on-and-off-and-on-again civil war that broke after the foundation of the “liberal” constitutional monarchy in 1834 (following another 27 years of intermittent warfare the Portuguese engaged in against both the French and each other), the State played a primary role in determining how wealth was distributed in the country, and to whom. Whether by giving jobs in the public sector to the clienteles of the parties (and even – perhaps especially, those parties’ bigwigs) that took turns in office, by creating tariffs that protected some economic activities from foreign competition, by establishing monopolies that protected some enterprises from national competition, or by channeling the taxpayers’ money (and the debt future taxpayers would have to pay for) into infrastructure projects that filled the pockets of those that were lucky enough to be involved in them or benefited directly from what they had to offer, the State – and the parties that occupied it even if only temporarily – almost singlehandedly decided who would get rich and who would pay (in taxes, higher prices or scarcity of goods) for the latter’s good fortune.

The 1892 bankruptcy put the whole arrangement in jeopardy. In just 18 years, the regime’s inability to share the increasingly diminished spoils of the national treasury around the hungry diners that sat at the budget’s table opened the way to the revolutionaries of the Republic, who from 1910 to 1926 ruled with terror and a strong voracity occupy every job the state had to offer with its supporters – and, just like their predecessors, themselves – without ever finding a solution to the problem that any Portuguese government has to deal with: how to simultaneously use the power of office to distribute wealth to those who sustain it and keep the public finances in a good enough condition so that a bankruptcy doesn’t preclude them from having anything to distribute.

It was that lack of an answer that brought in Salazar and his dictatorship. Commanding a secret police, he could enforce what we would now call an “austeritarian” fiscal policy, while applying an economic policy that, through protectionist tariffs and the condicionamento industrial – literally, the “industrial constraint” – ensured that a handful of big, politically connected economic groups enjoyed the pleasures of operating in monopolized markets. When Caetano replaced Salazar, the economy was slightly liberalized, but the coition between the government and the orbiting business interests remained basically the same, becoming, in fact, one of the major complaints of those who wished Portugal would become a “normal”, “European”, democratic country. But once democracy did indeed replace Salazar and Caetano’s authoritarian regime, and ended up avoiding being itself replaced by a communist dictatorship – whether such an outcome was ever a realistic possibility or not is a matter of some contention – it too would repeat the cardinal sin of all the regimes that had come before it. From the onset, every party that came into the vicinity of power, both at the national and local levels, raced to fill every available job with the “boys” and “girls” who eagerly waited for them within their ranks, with the bill being paid by those working in the private sector (Henrique Medina Carreira, a former Finance Minister turned pundit, once claimed that 60% of the population is directly or indirectly dependent on tax-collected money for their income, meaning that their living standards are payed for the remaining 40%). As the country joined the European Union – at the time still known as the European Economic Union – and the money from its “structural funds” kept pouring in, successive governments of both the center-left and the center-right kept expanding an insolvent Welfare State that by purporting to provide for those who need it and those who don’t ended up giving too little to the former and too much to the latter – mostly those who were already lucky enough to have been afforded with a public sector job -, and “invested” in bloated, often disastrous infrastructure projects that fattened the bank accounts of the companies contracted to build them – and the banks involved in those deals – but burdened everyone else with ever increasing taxes, necessary to pay for the rising debt levels the country put upon itself.

In Portugal, one often hears those on “the left” saying that “political power” is “held hostage” by “economic power” – big, powerful business interests – while those on “the right” complain that “the government” controls and imprisons “businesses”. But the – sad – truth is that in a country where the State is involved –directly or indirectly – in pretty much every economic area of activity, the market of free interaction between individuals and their respective preferences is replaced by the market of political influence and access, where outcomes are decided not by how much one agent is able to satisfy the wants of its prospective clients, but by who has the phone number of the right Minister, party official, CEO or “fixer”, and whose hand can better scratch the back of the person on the other end of the line. In a country like Portugal, both governments and business interests engage in a symbiotic relationship like that between a zebra and the oxpecker: the business interests that are within government officials’ ears finance their parties and engage in the “projects” those governments wish to promote so they can parade them in front of voters as propaganda in electoral campaigns, and in return, governments allow them to spend more money – that the State will later reimburse them for – than they were supposed to. Those same business interests are granted monopolies and guaranteed rents, like those given to the Espírito Santo group when it was privatized, and governments can say to voters that they helped “Portuguese businesses to remain in Portuguese hands”. Portuguese banks loan money to the State in an irresponsible fashion (reportedly about 80% of their exposure to sovereign risk is to the Portuguese government), and when those same banks reach the verge of bankruptcy, the State bails them out.

Caixa was essential element of this promiscuous relationship. When, after the economy as a whole and the financial system in particular were privatized and liberalized in the 1980’s and 90’s, and the country’s acceptance into the European Monetary System and later into the euro allowed for historically low interest rates, home ownership loans given out by Portuguese banks increased 773% from 1990 to 2000. Governments created incentives to those loans, not only helping banks in expanding their business activities and profits (at least until the crisis broke), but also themselves by creating in the voters’ minds the perception of growing prosperity (largely an illusion, as the fact that a large number of the non-performing loans dragging Portuguese banks down are home ownership loans demonstrates). Caixa, especially being the State-owned bank, was at the forefront of this credit bubble. Similarly, CGD was also very much involved – it was the bank with the largest amount of exposure to them – in the public-private partnerships governments contracted to their favored economic groups that gave the latter huge profits simply through the guarantees the State offered them, and the former the opportunity to both feed the construction bubble and dazzle the voters with big infrastructure “achievements”.

More importantly – and damagingly – Caixa has given governments the means through which to interfere in the economy, and therefore to give money to those they have wanted to give money to, often with the shadiest of purposes. For years, Caixa’s stocks in companies like energy behemoth EDP or telecommunications giant PT were used by governments to circumvent the European Union’s rules regarding the voting power of the State’s “golden shares” in those companies: through Caixa, governments could prevent those companies from doing deals those governments were not fond of, for whatever reason. When the Sonae group tried to buy PT, for instance, Caixa blocked the deal. Years later, PT was found to be involved in a series of dubious deals with BES (and the Sócrates government) which would explain why selling it to a private group not known for being amenable to such arrangements would be something Sócrates would not look kindly to.

In 2007, one of Caixa’s competitors, BCP, was going through an internal dispute. The government, at the time led by Sócrates, allowed Carlos Santos Ferreira – who was leading Caixa – and Armando Vara – a former Socialist Minister and a longtime personal friend of Sócrates, who has since been convicted of corruption charges – to leave CGD for BCP, and at the same time, Caixa loaned a large amount of money to a group of BCP stockholders – more prominently, Joe Berardo – using BCP stock as collateral, in order for them buy more stocks and gain control of the bank and ease Santos Ferreira and Vara’s ascent to power. They did, but years later, Berardo’s debt was too high for him to be able to pay it back, and Caixa had to take the loss. For all intents and purposes, the whole operation amounted to the Sócrates government using Caixa (and, indirectly, the taxpayers’ money that would years later be used to bail it out) to gain control of a private bank. As Jorge Jardim Gonçalves, who was pushed out of BCP by the coup, would later remark, by placing two politically connected people (one of them, Vara, someone whom he knew and was close with for years, and would also be tied to him in many of the scandals he’s being investigated for) Sócrates would be able to add BCP to Caixa – which he controlled by virtue of it being owned by the government – and BES – to which Sócrates was close (a proximity that is now also under investigation), and thus find it easier to loan money to the companies and business interests he’d wish, as well as to the State, to fund his growing need to buy votes with increased public spending without having to raise taxes in such a way that would scare voters away.

In 2006, when Santos Ferreira and Vara were still at Caixa, the bank invested heavily in a resort in Vale do Lobo. The deal was disastrous, resulting both in huge losses connected to Caixa’s 24% of the share of the enterprise, and to the non-performing loans with which CGD had financed the whole thing. Needless to say that Sócrates is also being reportedly investigated for a possible involvement in this deal, and how he and Vara might have profited personally from it. In fact, pretty much every bad deal Caixa is involved in has the Sócrates touch to it. For instance, in 2006, Sócrates wanted to make a big deal out of an announcement of a new factory being built in Sines, a small coastal town in Portugal’s southern region, and even handed out millions in tax benefits to facilitate La Seda’s – the company planning to build the factory – decision. Coincidently or not, Caixa invested in La Seda, and again ended up losing a lot of money in the process. The same happened with a Pescanova factory in Mira that Sócrates proudly used as a propaganda tool and that Caixa helped finance: in the end, Pescanova went bankrupt and Caixa was left holding its trousers in its hand, instead of getting its money back.

***

On May 2, the meeting between Caixa and Almeida’s representatives didn’t take place. The branch closed, and its future is certain: it will stay closed. The town’s people may protest, but they will remain powerless to escape the consequences of CGD’s crisis.

Depending on how things play out in the months and years ahead, the same could be said of the country as a whole. The heavy exposure of Portugal’s banks to their own country’s sovereign debt bonds is not just a symptom of the promiscuous relationship between business interests and governments: it is a dark cloud hanging over the country’s prospects. For now, the economy is growing, as Lisbon and Porto have become a fashionable tourism destination and foreign visitors spend their money in those cities hotels, restaurants and shops. But if for some reason the international economy slows down, Portugal’s will slow down with it, and probably faster than everyone else’s in Europe. If that happens, paying the interests on the debt it already incurred in might become harder, and getting new loans to fund all the spending governments in Portugal need to do might become possible only at impossible-to-endure interest rates. Banks like Caixa might not be able resist another shock like the one some-but-not-all of them were able to back in 2011.

If anything like that happens – and though relatively unlikely, such an outcome is far from impossible – Caixa branches won’t be the only businesses closing, Caixa employees won’t be the only ones losing their jobs, and the whole of Portugal will join the people of Almeida in feeling deceived.

alves.bm@netcabo.pt; @ba_lifeofbruno